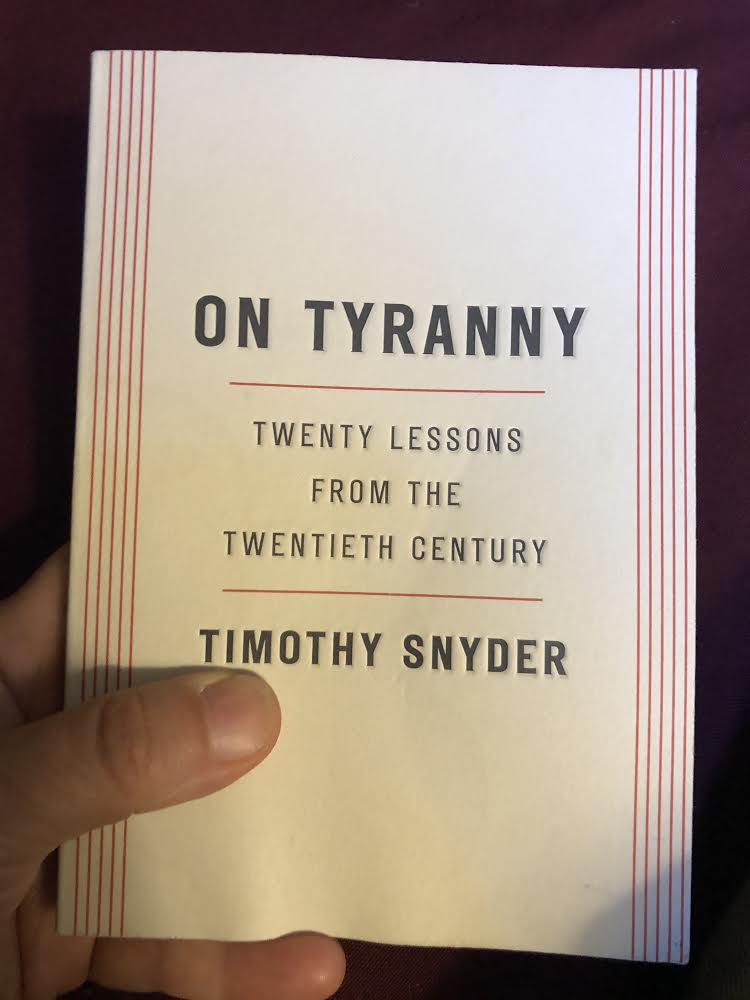

It’s the weekend, so I like to enjoy a little light reading while I sip my coffee. Today’s fare? “On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons for the Twentieth Century” by Yale University historian Timothy Snyder. Okay, so, it’s not light, but it is short. It’s literally a pocket-sized book—a very quick read. I highly recommend it to all of us who are worried about the health and stability of our democracy. Which, I very much hope, is most of us.

Its chapters are succinct and punchy and are organized around the premise that we need actionable strategies to prevent tyranny. They include: “Listen for dangerous words” and “Do not obey in advance.” The chapter I’m focused on this morning is called “Take responsibility for the face of the world.” Snyder reminds us, “The symbols of today enable the reality of tomorrow,” so we must be vigilant in identifying, naming, and publicly rejecting signs of hate. His instructions are straightforward: “Do not look away, and do not get used to them.”

One of the reasons Snyder’s work resonates so deeply with me is that his instructions for rejecting and dismantling tyranny are completely in line with the trainings that I do on authentic leadership. I remind participants in my trainings that trust is built in thousands of tiny moments of interaction. Good leadership is rarely about grand gestures. It’s found in the day in/day out conversations we have and decisions we make.

Snyder writes, “The minor choices we make are themselves a kind of vote, making it more or less likely that free and fair elections will be held in the future. In the politics of everyday, our words and gestures, or their absence, count very much.” Yes! Whether its Stalin using proganda posters portraying prosperous farmers as pigs, or Trump telling us that immigrants are rapists and murders, these messages are meant to signal to us that it’s okay to dehumanize others. Snyder: “A neighbor portrayed as a pig is someone whose land you can take.” So, too, an immigrant who you’re taught to fear is someone you can attack physically.

He ends this chapter by reminding us of Czech dissident Vaclav Havel’s words about complicity and propping up a regime. Under tyrannous governments, citizens are asked to display signs of loyalty. Some citizens will choose to adopt them—not because they believe in them or the regime—but because they want to be left alone. They want to carry on life as before, and if the price is to post some propaganda slogan in the window of their shops, they will do it so they can steer clear of the authorities. But this desire to be left alone, to not fight or stand up against tyranny, allows the regime to dig its roots deeper.

“[B]y accepting the prescribed ritual, by accepting appearances as reality, by accepting the given rules of the game, [it makes it possible] for the game to go on, for it to exist in the first place,” said Havel. Snyder reminds us that we don’t need to play the game.

Havel gave the commencement address for one of my graduate degrees in 1995. Snyder’s book reminded me to go back and re-read the speech. He ruminated on the task for politicians in the modern age: “Their responsibility is to think ahead boldly, not to fear the disfavor of the crowd, to imbue their actions with a spiritual dimension…to explain again and again—both to the public and their colleagues—that politics must do far more than reflect the interests of particular groups or lobbies. After all, politics is a matter of servicing the community, which means it is morality in practice.”

Both citizens and politicians bear the responsibility of fighting tyranny. Use the power we each have for justice, for good, for the very future of our democracy.