I’ve found it tough to write lately; in moments I feel both agitated and unfocused. I know anything I write has already been said—many times over—and in tighter, more clever ways. But something’s been haunting me, and I want to try to organize my thoughts and write about them. Even if they fall short of my expectations and standards. Even if they only reach a few souls. Because I’m trying to make sense of this national mess we’re in and help us find a way out.

Here’s the question that’s been popping up in the quieter moments—when I’m driving, when I’m walking in the woods, when I just close my eyes and breathe deeply: How do we reach some of the millions of Americans who’ve completely accepted Trump’s propaganda?

This is not a rhetorical question for me. I mean it most sincerely. I know we can’t hope to reach all of them; some have been completely blinded by the cult of personality that is the Trump brand. And no, I’m not talking about the Trump business enterprise with the family name garishly posted on buildings and products. I’m referring to his presidency itself, which long ago ceased to be about ideas or policy. It’s a classic case of a cult of personality. All the parts are there: relentless propaganda, big lies, government-organized demonstrations, constant flattery and praise from his underlings, stoking feelings of hatred and resentment, giving people permission to feel aggrieved and angry, and providing the public with enemies to blame for all that’s wrong in the nation.

Needless to say, this is all grotesque. And my revulsion at this twisted cult makes me want to avert my eyes, turn away from the news stories and videos. I want to go inward and self-protect, which is a natural reaction to discomfort and disgust. But as a historian, as a teacher, and as a politician, I do feel a responsibility to keep watching and witnessing. And to share information, instruct, and make connections when I can. And to turn to others who can help guide me in this work.

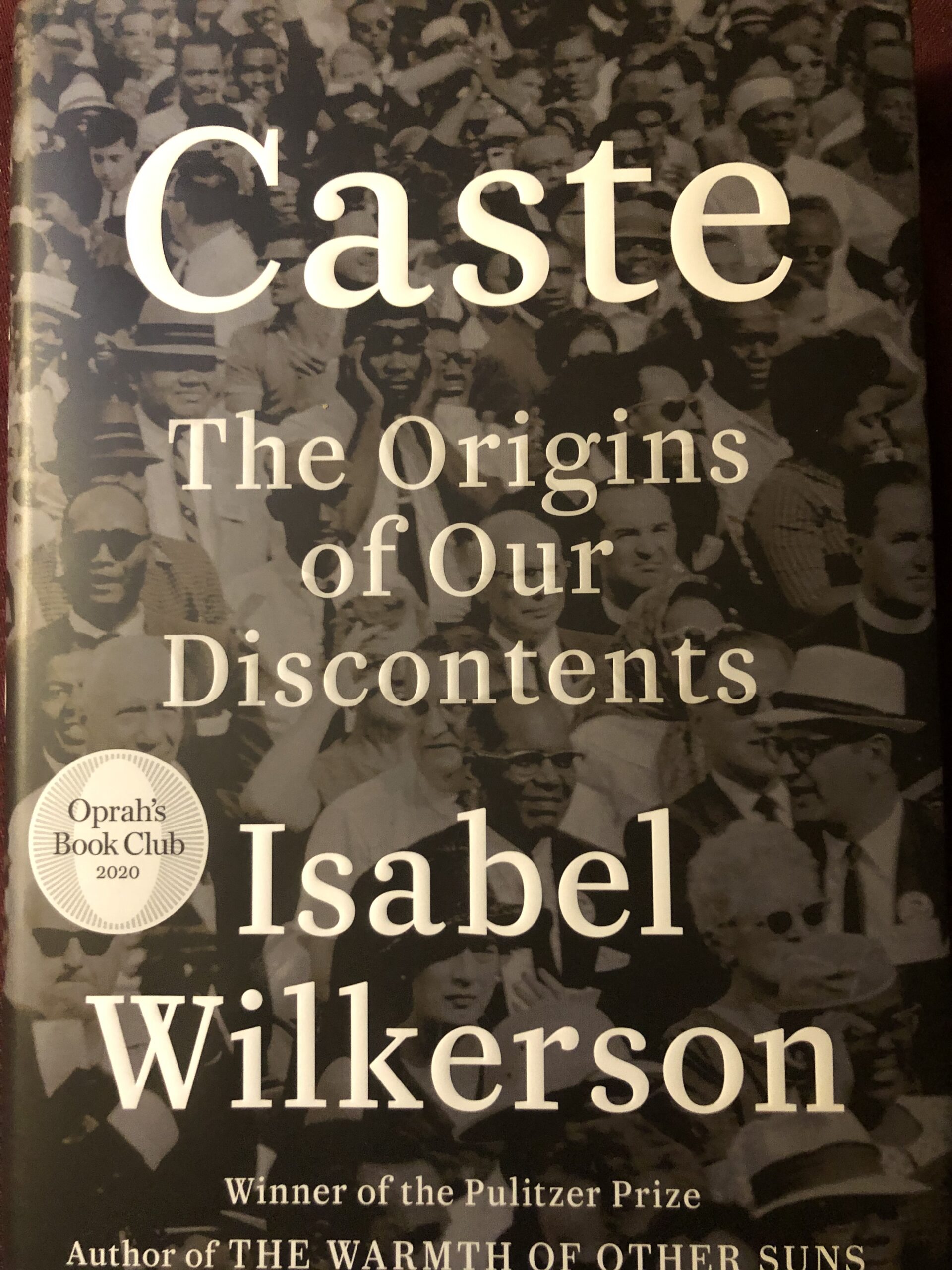

Let me make something explicit: what we’re seeing now is not new. It is the inevitable outgrowth of a society built on a caste system. This Trumpian moment is (I think) the last ugly gasp of a hierarchy built over hundreds of years in this nation. But this excruciating “moment” may last for years if we don’t see it for what it is: the clash between those who want to finally dismantle our often hidden caste system and those who believe their only hope of maintaining any kind of power is in keeping the caste system intact. Thank you, Isabel Wilkerson, for giving me and thousands of other Americans the incredible gift to the nation that is your latest book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. It’s so damn good. There’s a reason Oprah Winfrey sent 500 copies of the book out to our nation’s governors, mayors, CEOs and college professors. It lays bare the failure of our nation’s ideals—ideals that were written while the caste system was already in place.

I know that so many people will never willingly read a non-fiction book, no matter how emphatically I tell you that you should, so I’ll highlight a few passages from Wilkerson’s book that I hope will stay with you and give us all courage and strength. If we truly start to understand and accept that our caste system based on skin color has been built over hundreds of years, we will not lose heart so quickly when it inevitably takes so many years to dismantle it. Bottom line: The American caste system began in earnest after the arrival of the first Africans to the Virginia colony in 1619.

From Wilkerson’s book: “It is a measure of how long enslavement lasted in the United States that the year 2022 marks the first year that the United States will have been an independent nation for as long as slavery lasted on its soil.” It doesn’t matter how many times I read this sentence; it still shocks me.

Many Americans still see slavery as that “peculiar institution” that was an unfortunate, but short-lived, aspect of our nation’s past. And most have no idea of the political gains made by African-Americans during the period of Reconstruction–or how the racist “Redeemer” movement in the South put the racial caste system firmly back into place through terror, intimidation and the might of the Jim Crow laws.

Wilkerson, again: “The institution of slavery created a crippling distortion of human relationships where people on one side were made to perform the role of subservience and to sublimate whatever innate talents or intelligence they might have….On the other side, the dominant caste lived under the illusion of an innate superiority over all other groups of humans, told themselves that the people they forced to work for up to eighteen hours, without the pay that anyone had a right to expect, were not, in fact, people, but beasts of the field, childlike creatures, not men, not women, that the performance of servility that had been flogged out of them arose from genuine respect and admiration for their innate glory.”

And then these warped relationships were passed down from generation to generation. And those in the upper caste grew used to their “unearned deference” and came to expect it and demand it. As Wilkerson points out, as they dehumanized others, they dehumanized themselves.

It is this lie—this wicked distortion of human relationships—that we, as a nation, are finally confronting. At least, some of us are. The others, those not ready to confront the lie, are the ones who are grateful for Trump’s message. He’s buying them a bit more time to live in the sick enchantment of the lie. He’s giving permission for their sense of aggrievement. He’s blatantly harkening back to a time when the caste lines were clearer. A time when a Black man couldn’t be president; a time when a woman of Indian and Jamaican descent could not be a candidate for Vice President.

His propaganda is comforting to those who don’t truly understand our nation’s fraught history, and it bolsters those who are deeply afraid (sometimes unconsciously) of losing their power, their station. But sharing power does not mean a loss of power. Inviting more people into places of power means that as a nation we might finally be able to fulfill the noble, but so far unrealized, ideals of equality and justice.

So, back to where I started. How do we reach some of the millions of Americans who’ve completely accepted Trump’s propaganda? I don’t know for certain, but I do feel a little closer to the answer after reading Wilkerson’s magnificent book. We must all start to make America’s invisible caste system more obvious, and we must honestly name the ways in which this tight system of control keeps us all smaller and more fearful. It’s a terrible way to live.