(This is the text of a sermon I gave on November 22, 2020 at the Mount Mansfield Unitarian Universalist Fellowship.)

I want to start my sermon with this simple truth: Stories are powerful.

They entertain, they instruct, and they can carry the force of history and the weight of tradition over hundreds–even thousands of years.

But we often ignore the power of our own narratives–the stories we tell about ourselves that may limit us or free us. So frequently, we underestimate the extent to which we can change the stories that we tell about ourselves. Today I want to propose to you that we are writing a critical chapter in America’s story: the story of an ongoing, unfulfilled quest for liberty and justice for all.

One story that has deeply shaped my family and me is the story of what happened to my grandfather in the spring of 1945.

On April 22, 1945, my paternal grandfather, Leopold Bálint, (Leo to his friends and family) was killed on a forced march from Mauthausen Concentration Camp just two weeks away from the camp’s liberation. My grandfather Leo stopped to assist another ailing prisoner. He knew, as they all did, that stopping along the march meant certain death, but like so many others–before and after him–his humanity and empathy overpowered his fear. Leo wrapped this man’s arm about his shoulder, put his own around the weary man’s waist, and dragged him along for a short distance. His already low reserves were soon spent, and they fell dangerously behind the group. As eyewitnesses informed my grandmother afterwards, both Leo and his comrade were summarily shot and their bodies heaved into the chilly waters of the Danube.

I know Leopold only from the family stories I have heard. But my grandfather’s murder has colored all of our lives. As Elie Weisel has written:

“Time does not heal all wounds; there are those that remain painfully open.”

My father and I, and now my son, too, we look a lot like Leo. Similar eyes and lips and chin. It is at once eerie and comforting. He lives on in our DNA; he is with us on a cellular level.

I inherited my sense of humor, my insatiable curiosity, and a deep love of history from both of my parents. But I also learned to be standoffish, even suspicious of neighbors.

My father was always, and remains, hesitant about connecting with neighbors. I used to chalk it up to European manners, but in my adulthood I have come to realize that this too is a scar of the Holocaust. Neighbors can betray you; indeed they did betray him and his family.

When my grandfather had a bathtub installed in their apartment building, the neighbors griped that “those dirty, stinking Jews are bathing too much.”

Or the worst story of all – the trusted teacher who gathered information from his young students about who had Jewish parents. One ongoing toll of the Holocaust and indeed of all totalitarian regimes — beyond the destruction of families, the loss of faith, and the enormous grief — is that we start to doubt our neighbors’ basic humanity. We come to believe it’s safer to keep them at a distance because people can sometimes be so horribly callous.

This is the family story I am trying to change. I believe strong neighbors make strong democracy.

It helps that Vermont’s size makes it a state of neighbors. My dad has slowly come to understand that my family and I love our town. We feel safe here. But he still occasionally comments about his personal discomfort with small town life. One of the first things he asked when we bought our house in Brattleboro was: How are the neighbors? Will they accept your family?

He worries that the country still isn’t really accepting of an openly gay politican. He worries that neighbors can betray.

Writer Daniel Goldhagen argued in his controversial 1996 book Hitler’s Willing Executioners that many Germans were willing to participate in the final solution because German culture and society had indoctrinated them in “eliminationist anti-semitism.”

Many historians excoriated the book, maintaining that his research was shoddy and that Goldhagen ignored any material that did not prove his thesis. But he still became something of a celebrity on his book tour in Germany.

Despite its academic shortcomings, the book resonated with many Germans. They understood that Hitler’s ghastly plans were only set in motion because average people told themselves there was nothing they could do. They chose to look the other way.

When faced with these stories of atrocity, of complicity, and of bravery, we often ask ourselves: Would I have had the courage to stand up and do the right thing?

But most of us will never be faced with such a stark situation, so I think that this is perhaps the wrong question. The real question is: Do I have the courage, day in and day out, to show kindness to and concern for my neighbors?

The small gestures do matter. When I bake bread for a neighbor (even if our politics don’t align) or check on another when she’s sick (although she sometimes talks my ear off), I’m asserting that there is still basic humanity in the world. I do it for me, for my parents, for my children, and for their great-grandfather, Leopold Bálint who retained his humanity in the midst of the depravity.

And now, I do it, too, for my nation.

Like many of you, perhaps, I thought that we were farther along in our evolution as Americans, as human beings. But these past four years have revealed just how far we still must go on our national journey towards true justice. At times, the work feels so overwhelming and so tiring.

It’s easy to lose hope. It’s easy to give in to despair.

But I want to remind you all–We are not the same people we were on election night in 2016. Many Americans are newly activated, finally turning out to vote in large numbers. Finally taking to the streets to stand with our Black and Brown neighbors. Finally truly understanding that democracy only works if we participate. We must be all in.

I sense a new awakening inside so many Americans and an understanding that this experiment in democracy is actually pretty young and, as it turns out, pretty fragile. We have to commit to fighting for it. We have to feel the urgency and the purpose. I know we will come out of this darkness, but we must be focused and determined.

On election day, while standing at the polls, I had the lyrics and music of singer/songwriter Bernice Johnson Reagon in my head. She wrote these words based on the writings of civil rights activist Ella Baker.

We who believe in freedom cannot rest. We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes.

Ella Josephine Baker was a truly remarkable woman. It’s astounding that so many Americans don’t know her name and her work. She was a highly effective civil rights and human rights activist. Baker did most of her work behind-the-scenes, living her ferverent belief in on the ground organizing.

Baker’s work spanned more than half a century, and she worked alongside WEB DuBois, Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King Jr. Baker also mentored emerging activists like Stokely Carmicheal and Rosa Parks. Her talents touched so many aspects of the civil rights movement. And she played a key role in many of the most influential organizations of the time: the NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Baker believed that we can ignite change by uncovering and using the power of regular people to reshape our communities, to write our own stories and to shape our own destinies.

Ella Baker, like so many black women before and after her, knew that we have no time for despair. We do not have the luxury of losing hope.

As I said, her words were on my lips and in my head on election day this year. As I sang them softly,

We who believe in freedom cannot rest

I felt anticipation and excitement. It was the same kind of stirring I felt back in ‘08 when I made calls into PA for the Obama campaign.

It’s this feeling that we are on the verge of a new generosity of spirit, a renewed commitment to justice and righteousness. An understanding–a great realization that we all truly have a part to play in this big change– the shift towards being willing, being finally willing, as a nation to confront our demons and our shortcomings.

For too long, people of color have done this work in the face of opposition from even well-meaning, left-leaning white people. We must join with them to continue this work. To pick up where Ella Baker and Dr. King and John Lewis and Shirly Chisholm left off.

If we do it right, it will be our children and our children’s children who will finish it. And the generations who come after us will continue to be vigilant to protect this republic that we were able to pull back from the brink. That is the story I am telling myself. And I hope you will join me in the telling.

I do not have rose colored glasses on. As I said, I am the grandchild of a man murdered in the Holocaust. I know people can be horribly cruel and inhumane. But I also know that racist and xenophobic populism can be defeated, it must be defeated, it will be defeated. Because there are more of us who are ready to fight for justice than there are Americans who feel comforted by our president’s flirtation with facism.

There are millions of us bound together. Millions together in this commitment to each other and to our nation.

We who believe in freedom can not rest until it comes.

I started my remarks this morning with acknowledging the power of stories to help shape us and to give our lives meaning and purpose. And I reminded us that we have the power to rewrite our stories, our personal stories and the stories we tell about our nation.

As a historian, I’m keenly interested in the story that will be told about the past four years and about this election.

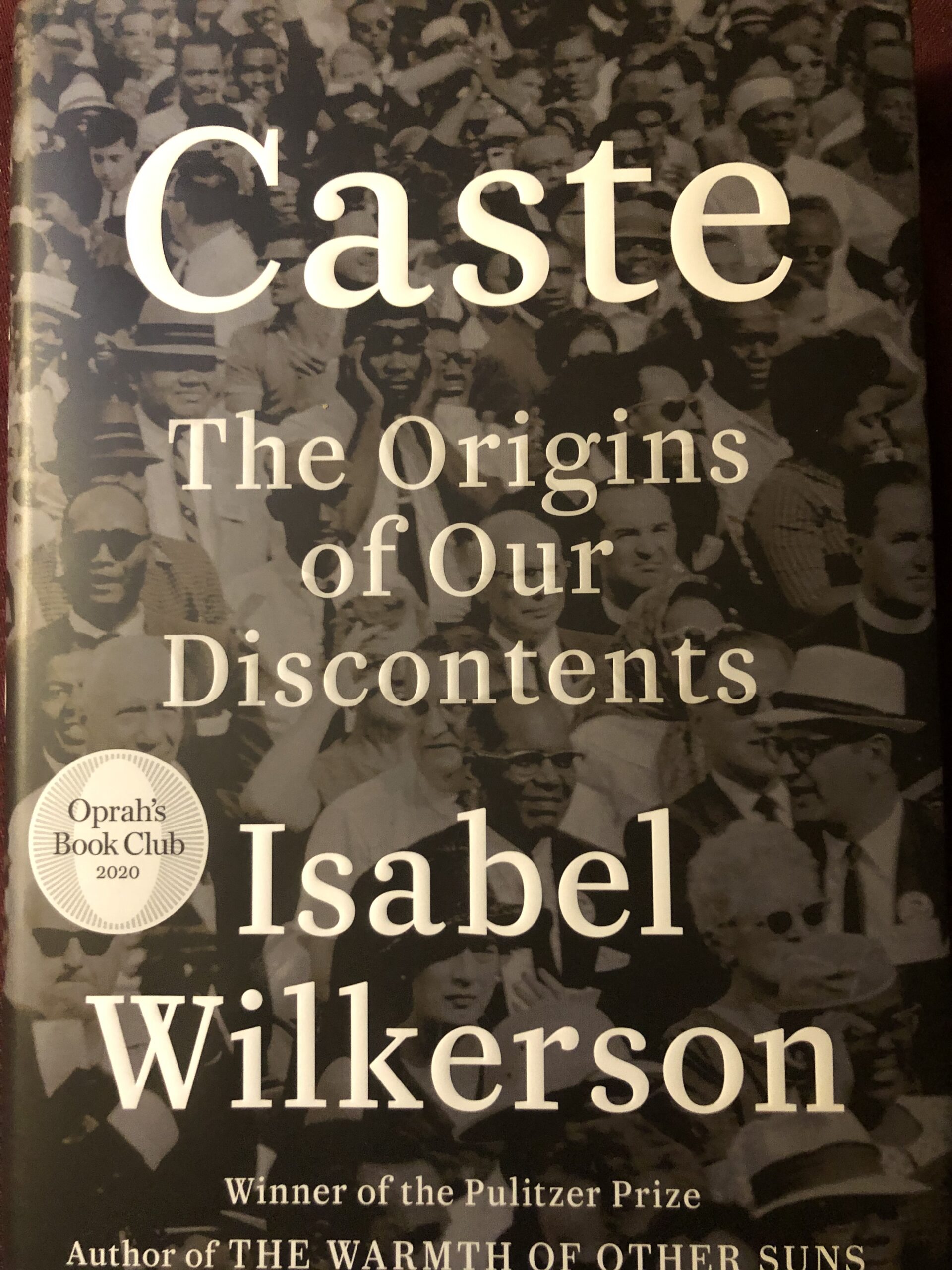

The story of this election victory is, undoubtedly, the story of the labor of black women. Black women voters are the most formidible and consistent voting bloc for Democratic candidates. Period.

Let me say this clearly because in a state like Vermont it can be hard to believe: more white men voted for Trump than for Biden. More white WOMEN voted for Trump than for Biden.

America has been saved from the destruction of our republic because of the fierce organizing of Southern Black women like Stacey Abrams, who launched Fair Fight, and LaTosha Brown, who co-founded Black Voters Matter.

Abrams didn’t cry in her coffee after the ongoing voter suppression in her homestate blocked her from victory in the Georigia gubernatorial election. She felt there was no time to mourn; she had to organize. She– like so many other black women before her–did the nation’s labor.

As Rutgers professor Brittney Cooper has pointed out: “Black women leaders are so important to this democracy precisely because they dare to keep dreaming, even after the immediacy of a perpetual nightmare like Donald Trump.”

Joe Biden was able to win because of black women.

Kamala Harris was able to win because of black women.

The president was beaten at the ballot box because of black women.

The stories we tell about this election, about our nation, must be rooted in an enduring truth:

We will never fulfill the promise of our nation’s ideals without black women at the table, in the halls of power, in our national psyche.

These women inspire me in my own work. They give me courage when it falters. They give me strength when I have self doubt.

Years ago, I got some simple advice that has stayed with me–what people think of you is none of your business. You can’t control what is said about you, how it is interpreted, or how far the stories will travel.

What we can control are the Stories that we tell about ourselves. And how we allow ourselves to be moved and inspired by meaning making.

I am about to be elected the first female president pro tem in the history of the Vermont Senate. I will also be the first LGBTQ legislator to lead either chamber.

This will be an exciting moment for so many people across our state, and it will be scary and intimidating to others, including some of my senate colleagues, I’m sure.

My election to the position of president pro tem will be unconsciously (and perhaps consciously in some instances) perceived as a threat. I challenge long-held ideas about what a leader looks like. I will have to find a way to address these concerns within the senate without elevating the naysayers or ignoring their fears.

A key to successful change is bringing people collectively into the conversation about solutions and highlighting for them the ways in which sharing power will not necessarily diminish their own power AND in fact will probably lead to better outcomes for all of us.

As we do this work, this work of collective action towards justice, we need to help each other to continue to pivot towards hope. We have to channel our curiosity and wonder and our belief that we really can make positive change. We have to help each other have difficult conversations. We have to help each other imagine new and different endings. We have to tell new stories about who we are, and what this nation can become. It’s the only way through.

I’m humbled and frankly, a bit daunted by the task ahead of me, but I know that I’m not alone in this work. Millions of us are in this together.

My grandfather, whose smile I inherited, will be with me as I work alongside all of you to protect our democracy and to serve the community of man.

.